This blog was written by Isabelle Dyson, Expedition Program Coordinator, with support and partnership from our friends at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

The seasons in Maryland are immutable. Without a doubt, spring will arrive with rolling rain clouds, the summer will pass with afternoon storms, and fall will approach with dropping leaves and a cool breeze.

Fall is always a special time on the Appalachian Trail. It was the first time I ever went on the A.T. for Chesapeake Bay Outward Bound School (CBOBS), when the leaves had just started to turn and it was chilly enough to start my hike in a jacket and ditch it by the time I got to the top.

At the time I only worked on local programs in Baltimore and had begged our expedition team to let me join them on the A.T. for a day. I was enamored with the idea of seeing students “out in the wild,” climbing rocks that are tens of millions of years old. I took a bunch of pictures and sent them to anyone I could, in awe of the fact that I got to do this as a job. The following year I chose to become an expedition instructor as well, and got to go on my first courses with our students.

Growing up, I was a model student. I strove for straight As, tons of extracurriculars, and perfect attendance. When I grew into adulthood, it hit me like a ton of bricks that I no longer had that traditional school structure to guide my goals. The more I learned about traditional schooling, the more I bucked against the idea that it was the best way to teach the youth of today. So, I chose the next logical path: becoming an outdoor educator.

As an outdoor educator, you quickly learn the importance of balancing learning with emotion. The students we take on course encounter an entirely new environment, paired with spending 24 hours a day with classmates they may have never spoken to before. We ask them to trust us almost immediately with their safety and wellbeing and then ask them to stretch their comfort zones in ways they didn’t think were possible. We throw acronyms at them, ask them to do silly dances, and push them to hike or canoe more miles than they maybe ever have. An Outward Bound course is potentially one of the hardest life experiences they’ve had yet, and we have the daunting task of hopefully making it pay off.

The outdoors can often feel restrictive in the ways we are asked to interact with it. Students can often feel limited in their exploration amid the drudgery of the day-to-day tasks. One of my goals is to foster that love and appreciation for nature, and try to extend that to their home.

Much of the flora and fauna that we encounter along the Maryland section of the Appalachian Trail can be found in their own backyard in Baltimore, if one knows the right places to look. Instructors bring printouts of poison ivy, ticks, birds, and tree identification to help foster curiosity. Along with asking them to spend the night on the forest floor, we are asking them to accept, respect, and preserve the land that we travel on. For many of them, this is as novel as asking them to become fluent in a language overnight. We teach them navigation, trail etiquette, flora identification, and Leave No Trace principles within the first day. And like the sponges that they are, many of them soak up that information immediately, and with joy.

The A.T. serves as a magical, one-of-a-kind classroom. You are experiencing the dichotomy of the Rocky Run shelter one day, with its swift-moving spring that looks good enough to take a dip, followed by the Dahlgren backpacker site, with its flushing toilets and hot water showers.

The MD section of the A.T. is only 41 miles long and contains some of the gentlest terrain the trail has to offer. Maintained by the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), this section of the trail offers plentiful campsites, shelters, and well-maintained ground. Backpacking can feel inaccessible to some students, and unheard of to others. My hope in working at CBOBS is to make that inaccessibility feel a little smaller. Having the world’s longest hiking-only footpath as my office feels uniquely special.

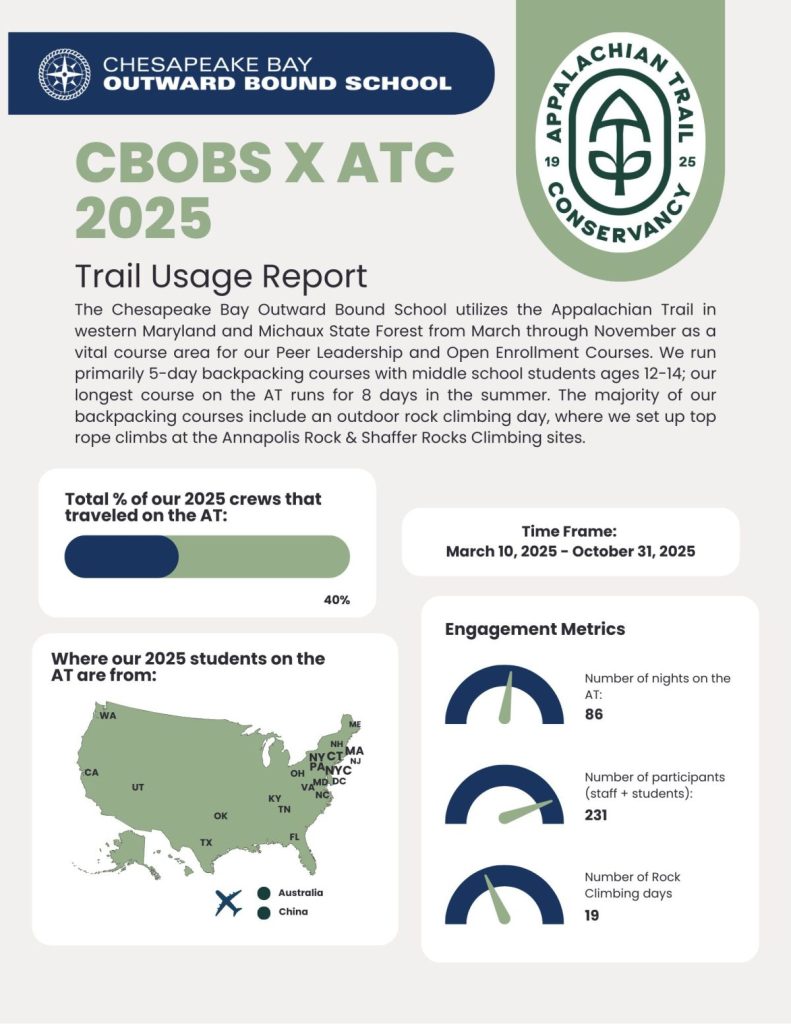

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy is the only nonprofit responsible for protecting and managing every mile of the A.T., from Georgia to Maine. Working in partnership with 30 local Trail Clubs, the ATC helps foster a safe, welcoming, and transformational experience for Trail visitors by providing training, resources, and on-Trail support.

In 2025, 4,592 volunteers contributed more than 155,000 hours to maintain the Trail’s tread, shelters, and scenic corridors. The ATC and their partners also coordinate the A.T. Ridgerunner program, which places seasonal educators along heavily used sections of the Trail. Maryland Ridgerunners play a vital role in group outreach, helping ensure that organizations like CBOBS can enjoy the Trail responsibly while fostering a lifelong connection to the outdoors. At popular course destinations like Annapolis Rocks, a single Ridgerunner or caretaker may interact with nearly 7,000 hikers over an eleven-week season. Many of our programs utilize sections of the Appalachian Trail, and in this manner the ATC’s work supports our educational approach.

The youth of today are incredibly resilient. I am constantly amazed by how much they can teach me. I am often laughing, contemplating, and questioning more on the trail than I ever thought possible. When I am not on course with students, I try to seek opportunities that will spark those same slightly nervous, unsure feelings that they have at the beginning of our expeditions.

Last year I had the privilege of attending the Emerging Leaders’ Summit with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. I met people who loved the outdoors as much or more than I do and spent time expanding my perspective of the A.T. and the people who utilize it. I spent time with some of the PATC Ridgerunners, who dedicate their time to hiking, maintaining, and educating on the trail. We hiked a new-to-me section of the A.T., spotted a bear, and watched the sun rise over the valley. We learned new ways that people interact with the trail and bonded over our mutual love for the outdoors.

At the beginning of the weekend, I started out with the same nervousness that I imagine a lot of our students feel at the beginning of course. I had to meet new people, start conversations, and sleep in a cabin next to someone whose name I had just learned. By the end of the weekend, I was desperate to get everyone’s number, start a group chat, and plan our next meetup. I was reluctant to let go of the memories we had created and the space we had shared.

The trail feels like something that I can always return to. It is ever changing and feels both new and old upon every return. It is always teaching me something new. Resilience, patience, growth, and eternity. I aspire to be as steadfast as the Annapolis Rocks climbing site, as dependable as the Tumbling Run spring, as exciting as the High Rock Overlook, and as novel as Pen Mar Park.

When our students act surprised that we choose to do this for a job, I try to show them how inspiring it can be to have a boss like nature. And I try to remind them that they too have the capacity to be like the trail: ever-changing and steadfast.

Through partnerships and education with groups like the ATC, Chesapeake Bay Outward Bound School provides students opportunities to experience the outdoors and the Appalachian Trail safely and responsibly. The Appalachian Trail’s Mid-Atlantic section is a hub for outdoor learning and group adventures, thanks to the ATC, the volunteers, and Ridgerunners who keep it thriving. Learn how you can help keep the Trail alive and how public lands help shape experiential learning.